Commentary: Presidentially corrected economic talk

Published in Political News

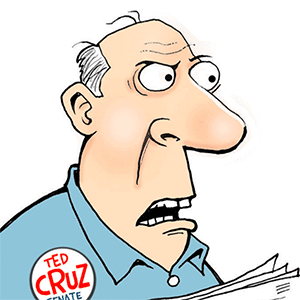

Whether U.S. bombers recently “obliterated” Iran’s nuclear capability (President Donald Trump’s preferred wording) or “severely damaged” it (per the CIA) matters so much to Trump that he’s threatened to sue news outlets reporting the CIA’s terminology.

The common presidential desire to shape the narrative has been especially noticeable lately, especially with matters regarding tariff-induced inflation.

It may even be generating a particular form of presidentially corrected economic speech reminiscent of Jimmy Carter’s tenure.

In 1978, Carter, worried about America’s sagging economy, ordered cabinet members to refrain from alarming the country with the word “recession.” Minding his boss’ instruction but facing a direct question, economic advisor Fred Kahn famously responded, “We’re in danger of having the worst banana in 45 years.”

With U.S. first quarter GDP growth now charting -0.50% and more than one respected forecaster looking at paltry growth later this year, will we see officials dancing around the same word in the near future? Trump’s preference for political happy talk has already reframed conversations about his economic agenda.

Trump recently chastised Walmart executives when they announced that China tariffs would force the retailer to raise prices. He angrily called for Walmart to “eat” the tariffs and reminded them in less-than-gentle terms that he would be watching.

In another example, toymaker Mattel indicated that it too would be raising prices because of tariffs. Outraged, Trump threatened to impose a 100% tariff on its products, promising the firm “won’t sell one toy in the United States.”

Since then, business leaders have been avoiding speaking about the price increases and other disruptions that Americans are quite obviously experiencing due to White House tariffs. As Neil Saunders, director of Global Data Retail, warned: ”The White House has decided it should aim its tanks at companies that do speak out.”

So, when offering investor guidance, some retailers speak of “adjusting” prices, others address the elephant in the room “gently and sparingly,” and still others refer to their pricing policies with words like “surgical.”

Above all, linking price changes to tariffs is a no-no. Denise Dahlhoff, director of marketing and communications research at the Conference Board, advises executives to use more neutral terms like “sourcing cost” or “input cost” or “supply chain cost,” which “are not as incendiary as ‘tariff.”

After all, Trump is serious about language. In February, the White House banned an Associate Press reporter from press conferences and Air Force One over the news agency’s refusal to re-term the Gulf of Mexico as the “Gulf of America” in its influential style manual (at least until cries over First Amendment rights turned the tide).

Trump and Carter are hardly the first pair of presidents to pour rhetorical oil on troubled waters, but the historical results, as with today, are mixed at best.

In Harry Truman’s time, the Korean War became known as a “police action.” Somehow the phrase softened the perceived scale of the situation and suggested the conflict would end quickly. But mid-century Americans knew a war when they saw it. Losing political patience, voters turned away from Truman’s party and chose Dwight Eisenhower to bring the action to an end.

In later wars, mostly undeclared, political speech began to deny the use of the word “retreat” in favor of terms like “an orderly withdrawal of troops.” Observers may view Vietnam or Afghanistan as the former, but leaders prefer less dramatic and more positive language.

Perhaps the most audacious and enduring effort by a Western leader to alter political speech came in 1604 when newly installed King James I of England ordered 47 leading Biblical scholars to develop a new Bible translation. The resulting King James Authorized Version is thought to be one of the most beautifully written volumes of the age. By the king’s order, it also removed certain references to kings as tyrants which had been present in an earlier English Bible.

Kings, democratically elected presidents, and holders of lesser offices will always frame things as they see fit, especially if they feel that their power or wisdom is being questioned. We the people may sometimes respond pragmatically by altering our own language. These things can be weathered so long as Americans retain our reverence for freedom of speech. Otherwise, only the bravest will have the gumption to call a spade a spade.

_____

Bruce Yandle is a distinguished adjunct fellow with the Mercatus Center at George Mason University and former executive director of the Federal Trade Commission.

_____

©2025 Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments