Editorial: In Jeffrey Epstein matter, powerful men slither away

Published in Op Eds

We’ve said little about Jeffrey Epstein, the serial sex offender who wormed his way into the upper echelons of elite America in no small part by trafficking underage teenage girls to powerful men. The affair is sordid, the conspiracy theories legion and much of the media coverage both exhausting and troublingly salacious.

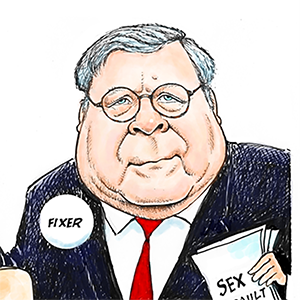

But on Monday, the Justice Department issued a memo that sought to put an end to the matter of Epstein, following what it said had been an exhaustive investigation. In essence, the government told the American people, “Nothing more to see here. Please move on.”

“This systematic review revealed no incriminating ‘client list,'” the memo said. “There was also no credible evidence found that Epstein blackmailed prominent individuals as part of his actions.” A little lower down, the government also says that investigators had concluded with finality that Epstein died by suicide in his cell at the Metropolitan Correctional Center in New York City on Aug. 10, 2019.

We’ve never doubted that Epstein killed himself. And we’re willing to take the Justice Department at its word that Epstein never blackmailed anyone, at least in any kind of formal way (although he did once strongly imply in an off-the-record conversation with The New York Times that he had the goods on many rich, powerful and famous men, with photos as proof). And it could well be also true that there is now no extant “client list,” depending on how you define the words “client” and “list.”

But what troubled us the most about the memo, and indeed this entire matter, is this statement in the memo: “We did not uncover evidence that could predicate an investigation against uncharged third parties.”

The question begged there is how hard did the government try?

Any fool knows that many powerful and well-known men were joining in Epstein’s sex trafficking activities at his homes in the U.S. Virgin Islands and elsewhere. Their names came up in the many civil cases surrounding Epstein, especially the one brought by Virginia Giuffre, who killed herself at her home in Neergabby, Western Australia, on April 25.

None of these men have admitted their guilt. Of all the men, only Prince Andrew has suffered notable reputational consequences, but even he has insisted on his innocence and remained uncharged and at liberty. Everyone else, often with the help of powerful lawyers and crisis PR firms, has been allowed to keep silent on the matter and quietly slip back into their normal lives. In some cases, the very newspapers that reported on Epstein in tones of moral outrage have then published flattering pieces about some who several victims have claimed were within Epstein’s orbit.

Notably, the people who have suffered the most in the Epstein affair are Giuffre, who appears to have been driven to suicide, the other girls whom he abused, and Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s friend, aide and co-procurer, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison on June 28, 2022. That’s not to say Maxwell, who denied the charges, did not deserve her sentence, but it’s still striking that all of the above are women.

The men, the Johns in common parlance, have been allowed to slink away — apparently now for good. Or, more accurately, for evil.

The logic of this seems to us irrefutable. Maxwell’s conviction was, after all, predicated on the existence of these men, as the jury at her trial heard and believed following testimony from victims. Epstein, we all know, did not hang out with ordinary people. He surrounded himself with the rich and famous. So if Maxwell did what the government successfully persuaded a jury that she did, then these men — about whom there apparently is no evidence that can be uncovered — must have existed, too.

Both sides of this divided nation have been hoping for the destruction of those on the other side. Republican supporters of Donald Trump had long hoped that the election of their candidate to the nation’s highest office would result in charges against several prominent Democratic figures, including some who held high elected office.

More recently, following Elon Musk’s charge (apparently made in anger and subsequently both walked back and to some degree reasserted) that Trump himself was “in the Epstein files,” the political calculus flipped, with Democratic partisans showing renewed interest in the Epstein case, concluding that Trump and those close to the president were allowing others to escape public humiliation and criminal charges to avoid embarrassment to Trump himself. (Trump, for his part, has said he cut ties with Epstein years before these incidents, has not been accused of any criminal wrongdoing in this matter and, notably, Giuffre said she didn’t think Trump was involved in sexual abuse.)

So. Case — or cases — closed, it seems.

What might ordinary Americans take from all of this? Some might argue that it is indeed time to move on from this sleazy business and, assuming crimes were committed here, these hardly will be the first perpetrators to remain uncharged due to a lack of evidence. Indeed, the U.S. system requires the presumption of innocence in absence of proof to the contrary.

But another likely conclusion, and one we arrive at ourselves, is that despite all the rhetoric about how the same justice system is applied to rich and poor, powerful leader and ordinary citizen alike, this case suggests otherwise.

And we wonder why so many Americans have become so cynical.

___

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments