Sam Cohn: A Preakness jockey taught me how to ride a horse

Published in Horse Racing

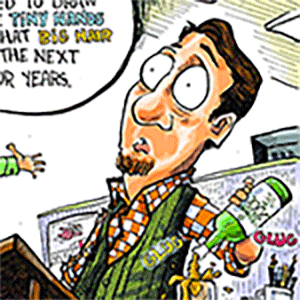

BALTIMORE — When I texted my family group chat that I’d be riding a horse for the sake of Preakness week content — pulling back the curtain of life as a jockey to see if I have what it takes — my mom replied with an iPhone photo of a grainy, printed out shot of her horseback riding 40 years ago.

That distant photo by association, and having jotted notes from the finish line at a pair of Preaknesses myself, were as close as I’d gotten to anything I did at sunrise last Thursday. The Baltimore Sun looked at this 5-foot-10 former high school basketball player with no discernible horse experience and said, “That’s our guy.”

That’s what made it fun.

Maryland-based jockey Sheldon Russell and his wife, Brittany, one of the most successful local jockey-trainer duos of the last half-decade, were kind enough to open their doors to myself and two ace photographers to learn more about a sport and lifestyle that, frankly, most people don’t think about more than one or two days a year — if at all.

I pulled into Laurel Park, taking the last drags of my morning coffee and moseyed over to barn No. 5 to meet the folks who would help me achieve this pseudo dream of being a jockey for the day.

Sheldon got in the game following in his father’s footsteps. Dean Russell rode in England, South Africa and Germany. His son was born in Louisiana, spent most of his formative years across the pond, then forged a career in Maryland. Sheldon is 5-6 (giant for a jockey) with a few new gray hairs and a sharp jawline that emanates English benevolence. His resume, in short, includes a second-place finish in the 2023 Preakness and a run in the 2012 Kentucky Derby, a year after earning the title of Maryland’s overall state champion.

Brittany became the first woman to lead the annual trainer standings in Maryland for her Uber-successful 2023. That was just her fourth full season. She’s the boss around here, a Pennsylvania native wearing a blond ponytail and a disarming smile. Brittany, in a less intimidating way, is to her horses what Bob Baffert and D. Wayne Lukas — two legends of the sport — are to theirs.

“It’s an everyday job, you’ve got to have a lot of dedication,” Sheldon said, his voice tightening for a moment. That in mind, we made our way over to a neighboring stable.

Sheldon leaned against the post, spun his head back toward the majestic steed behind him and said proudly, “We call this one, White Lightning.” I laughed because that’s a fantastic name but only later realized he was kidding. Someone told me his real name but, truthfully, I don’t remember, and whenever I retell this story, the pony will be known only as White Lightning.

Before climbing on, I had to get situated with the proper equipment. Russell handed me a padded vest. “It’s like a bullet-proof vest,” he said, “kinda.” I have no experience with those either. Then I strapped on a helmet, undoubtedly looking a bit goofy.

A more experienced horse rider would go for the stirrups and hop right up. I am not that. So they brought over a step stool to assist. Naturally, I tossed my leg over, grabbed onto the reins, looked into the camera and shouted some amalgamation of “the British are coming” and “yippee ki-yay.”

It wasn’t until later, while touring the jockey’s room, that I got the real lesson in how to be successful on race day, which, for a normal jockey, includes 4-5 races. The Equicizer in the lounge room was my batting cage.

An Equicizer is a mechanical, non-motorized horse. It’s used for training, exercise and therapy. This one was used to teach me the fundamentals of jockeying. Sheldon outfitted it with a saddle and reins. Then he handed me three pairs of goggles and a jockey’s whip. I turned to my photographer with a raised eyebrow that said, Oh, we’re really doing this.

So here’s what I learned in a morning’s worth of jockey school (I am obliged to share that Sheldon said I didn’t embarrass him).

The stirrups on a saddle sit much higher for racing than the ones I used for White Lightning, closer to the top of the horse. You’re in a deep squat, leaning forward, back parallel to the ground. Toes should be in the stirrups with heels driving toward the ground. It hurts right along the outer thigh. Keep your head up, too.

Sheldon tied the reins in what’s called a half bridge. My left hand clutched the knot and rested on the horse’s neck, my right served a few purposes: holding the rest of the strap, clutching the riding crop and managing my goggles.

Jockeys hold the stick toward the front of the horse rather than its behind. They’re allowed six “encouragements” per race and yes, they’re monitored (this year’s Derby winner was fined for exceeding the legal limit). It’s a clockwise wrist-twisting motion. That same hand has to reach up and pull off a pair of goggles when your vision gets clouded by mud — the trick is to pull down just one pair at a time, not accidentally rip all three, like I did.

The rest of the jockey room resembles any other clubhouse. Each has their own cubby, outfitted with silks and personal belongings. There’s an adjacent sauna-type workout room to make weight and a race-day scale — when I stepped on, Sheldon just shook his head and said, “This isn’t gonna work.” He opened up this brave new world to us novices. We returned to our cars with muddied shoes and a better appreciation for the craft’s interminable grind.

When I followed up on my family group chat with a picture of me riding White Lightning, my mom lied to me and said I look like a true jockey. “Any chance you could take over??”

No, mom. But now I know what to watch for on Saturday at the Preakness.

©2025 Baltimore Sun. Visit baltimoresun.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments