Reggie Leach was the final ingredient the Flyers needed to repeat as Stanley Cup champions in 1975

Published in Hockey

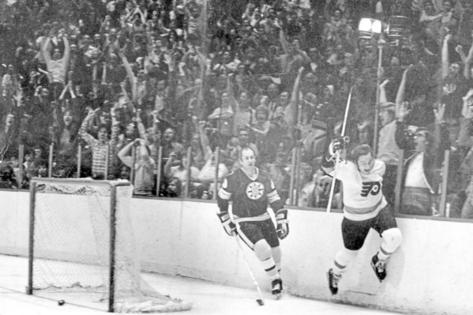

PHILADELPHIA — Fifty years ago Tuesday, Reggie Leach stood next to Larry Goodenough on the Flyers’ bench at the old Aud, watching as the clock ticked down. As the seconds decreased one by one, the defenseman turned to Leach and said out loud what everyone in the arena in Upstate New York and watching in Philly knew was coming.

“‘We’re going to win the Cup! We’re going to win the Cup!‘” Leach recalled Goodenough, who did not play that night but had come out of the locker room to celebrate, saying. All Leach could respond with was a less excited, maybe a little shocked, “Yeah,” as the two men hugged.

Leach, now 75, can’t recall much of what happened after that. It was a bit of a whirlwind when the buzzer went off, but he knows there were a lot of hugs, kisses and drinks out of Lord Stanley’s Cup.

What he does remember, with much disappointment, is how there was no passing around of the Cup from player to player back then on the ice. The captain, Bobby Clarke, got it and skated around as his teammates followed. If there had been a preset order, Leach would have probably come soon after Clarke — and not because he was his good buddy from their junior days in Flin Flon, Manitoba.

One of only four Flyers regulars who did not play on the 1974 Stanley Cup team — along with Goodenough, backup goalie Wayne Stephenson, and defenseman Ted Harris, who already had won four Cups with the Montreal Canadiens — Leach was a vital ingredient in the organization’s repeat.

A terrific trade

The acquisition of Leach came just five days after the Flyers hoisted the organization’s first Stanley Cup on May 19, 1974. Leach came east while Al MacAdam, Larry Wright, and a first-rounder were shipped to the California Golden Seals.

“Keith Allen had called me,” Clarke said of the Hall of Fame Flyers general manager. “The only time that, when I was playing, a manager had ever asked that question. And he called me and said, ‘Do you think Reg Leach would be good for us?’ And I told him, I said, ‘Reggie will score 35 or 40 goals in a bad year for us. If you can get him, he’ll be good for us.’ And of course, he traded for him.”

At first, it looked like a bad trade by Allen. Leach scored just four goals in the Flyers’ first 19 games. But then, a week before Thanksgiving in 1974, things started clicking with him and his linemates Clarke and Bill Barber. Leach would go on to score 41 over the final 61 games of the season.

“I had to start my whole career over again, the way I look at it,” Leach told The Philadelphia Inquirer. “I had to learn the system. I had to learn the game of hockey again. Because when I got drafted by Boston, I didn’t play there; I sat on the bench. When I went to California, we had a pretty good team when I first got traded there, but the second year the World Hockey [Association] came in, and I think we lost 12 or 14 guys the first year. ... We only won 13 games that year all year.

“I didn’t have very good work habits in California and stuff like that. And then when I came to the Flyers, I had to learn everything all over again. I had to learn what the game was all about, how to be a team player again, and it took a long time.”

His teammates were not worried. He was the new guy, and the system Fred Shero utilized at both ends of the ice took time to learn. “Everyone loves to score goals, but on the other hand, too, you’ve got to be accountable for defensive play and making sure that you’re not getting scored [on],” Barber said, sounding eerily like a recently fired Flyers coach.

After being given the time and space to grow, the winger nicknamed “The Riverton Rifle” by Allen was firing on all cylinders. He finished the year with a team-best 45 goals and 78 points, adding a still-standing club record of 61 goals the following year, and another 50 in 1979-80. Leach’s Flyers career spanned 606 regular-season games and saw him fire home 306 goals; he scored 51 in 171 games with the Seals.

The LCB Line

Skating on the LCB Line with his buddy Clarke (whom he stayed with when he first got to Philly) and Barber worked. The line — named after the first letter of their last names and also the initials of Pennsylvania’s Liquor Control Board — is one of the most famous in NHL history.

“It was just normal for us to be together. And we were lucky, because Billy Barber fit right in with the two of us,” Clarke said.

“We played together as a line for, I don’t know, about seven years or something, and they never broke us up,” he added. “When you play that long together, every shift together, you know what each other’s doing, and if someone’s not doing what they’re supposed to do that night, you tell them yourself. You don’t need the coach to tell you. So it became easy for us, as a threesome.”

Added Barber: “We kind of played off of one another. ... Reg and I had an agreement, when we had a two-on-one opportunity, our mindset was this: The only time we would pass to one another is if the defenseman really overcommitted to the puck carrier. ... I remember Clarkie to this day, God bless him, he’d [say] ‘Shoot, shoot, all the time.’ He wanted both Reggie and me to shoot the puck, and he made the great plays that were necessary for us to succeed, and just the whole line just clicked.”

Clicked is an understatement.

After Leach settled in, he found his game in a major way. Although his best postseason was in the 1976 playoffs when he scored an NHL-record 19 goals (tied by Jari Kurri in 1985) and was named the Conn Smythe winner despite being on the losing side, Leach potted eight goals and 10 points on the way to the Stanley Cup in ‘75.

But while the majority of his goals and points came with the LCB Line, the funny thing is that the Stanley Cup-winning goal came after a tweak to the line. Shero put Bob Kelly on the line instead of Barber to start the third period of the scoreless game. It took 11 seconds to make history.

“I just dumped it in around the net, and Kelly came in out of nowhere and hit Jerry Korab behind the net,” Leach said. “He stole the puck, and came right around the net and beat [Roger] Crozier. ... I was told when I first got traded there, if you get on a line with Bob Kelly: ‘Stay out of his way, because he just goes in a straight line.’ Doesn’t matter if you have an orange sweater on or a blue sweater on, he’s going after that puck.”

And that’s what he did.

The Flyers won that game, 2-0, with Bill Clement adding the insurance goal and Bernie Parent pitching the shutout.

“To me, to win the Cup was a dream come true,” Leach said.

Hockey as a ‘stepping stone’

Now living in Ontario, Leach will make his way over to the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto now and then. And if someone asks, he’ll take a picture with them and the Stanley Cup because going to Philly and winning it was “the thrill” of his life.

But it does not define Leach 50 years later.

A member of the Berens River First Nation, Leach has been open and honest about his past. On Sept. 6, he will be 40 years sober and he spends his time today as a motivational speaker and speaking to children about the bad choices he has made across his 75 years.

“I think as great a player as Reggie was, that was a short period in his life. He does much more with his life now and is a much more successful human being, helping his own people, than he was as a hockey player,” Clarke said. “And he was a great hockey player; he won a Stanley Cup. But alcohol almost ruined his life, and he came through it. ... He was a great person, but he wasn’t going to be if he was going to drink. He’s a special man.”

A member of the Flyers Hall of Fame and the Manitoba Hockey Hall of Fame, Leach has been awarded some of Canada’s highest honors, including the Order of Manitoba and, in 2019, the Order of Canada, the second-highest honor in the country. The same year, Leach also received an honorary degree from Ontario’s Brock University.

“All these things I have done after hockey, I’m more proud of what I have done after hockey than I did during my hockey days,” he said.

“You know, my life is really different now,” he added. “I went through the problems that I had as a hockey player, of being an alcoholic and stuff like that. ... Hockey, to me, is just a stepping stone to who I am today, and I’m a lot better person today than I was playing in the National Hockey League. So that’s what I’m proud of.”

____

©2025 The Philadelphia Inquirer. Visit inquirer.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments