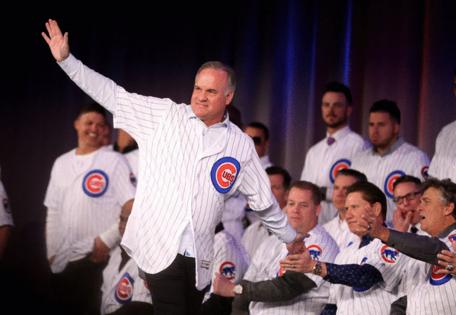

Paul Sullivan: Ryne Sandberg left a legacy at Wrigley Field -- and the Cubs and their fans were better for it

Published in Baseball

CHICAGO — Ryne Sandberg was more than just a ballplayer.

He was a man who changed a team, which transformed a neighborhood, which helped turn a bandbox ballpark called Wrigley Field into a mecca for baseball fans for decades to come.

Yes, the Chicago Cubs still would’ve played baseball if Sandberg had never worn the blue pinstripes with the No. 23 on the back. Wrigleyville still would’ve existed as another part of Lakeview, and a neighborhood made up of older residents in three-flats, corner bars with Old Style signs hanging out front and small businesses probably would’ve become gentrified in due time.

Wrigley Field might’ve lasted as long as it has without Sandberg’s star turn back in 1984, but who knows?

Suffice to say Sandberg’s memorable rise from semi-obscurity in summer ’84 — with the Cubs in first place in the midst of a 38-year pennant drought, playing day games in the only major-league ballpark without lights that were televised across the hemisphere on the WGN superstation, and with a perfect hype man in iconic broadcaster Harry Caray — led to a culture shift on the North Side that no one saw coming when he arrived two years earlier in a trade with the Philadelphia Phillies.

He didn’t completely erase the Cubs’ reputation as losers. That wouldn’t happen until 2016. But Sandberg helped usher in an era in which the Cubs were no longer a team that could be ignored and showed the world how magical a ballpark could be when everything worked.

Sandberg, who died Monday at the age of 65, will be remembered as a Hall of Fame second baseman, an all-time Cubs great and a man who played the game the right way.

Sandberg’s story can be told in numbers — the nine Gold Glove awards, the 10 All-Star games and the MVP Award in ’84.

But the real legacy of Sandberg’s career is reflected in the respect a laughable organization suddenly earned when he morphed into “The Natural,” a real-life version of Robert Redford’s movie character. A supporting player on some bad teams, he became a superstar one afternoon with two memorable swings against St. Louis Cardinals closer Bruce Sutter on a hot summer day at Wrigley with a national TV audience tuned into the “Game of the Week” telecast.

In 1982, Sandberg’s rookie season, the Cubs finished fifth in the six-team NL East and drew 1.2 million fans, finishing 10th in attendance in a 12-team National League. They finished fifth again in ’83, and though Sandberg won his first Gold Glove after switching from third base to second, he was considered slightly above average with a 3.7 WAR, and few fans outside Chicago paid any attention to the Cubs.

Then came ’84, when Sandberg took off and carried the Cubs through a dreamlike season, their first postseason appearance since losing the 1945 World Series. They surpassed the 2 million mark for the first time in history, drawing 2.1 million fans to rank second in the NL. Wrigley was no longer a playground for kids and a haven for retirees but the hottest ticket in baseball.

The “Sandberg Game,” on June 23, 1984, was Sandberg’s introduction to the rest of America. A game-tying home run off Sutter in the ninth, followed by another game-tying home run off Sutter in the 10th, led the Cubs to an electrifying win over the Cardinals and gave NBC announcer Bob Costas the call of a lifetime.

“The 1-1 pitch … left-center … do you believe it? … It’s gone.”

Sandberg was not a home run hitter at the time, though he had started pulling the ball more that season, at the request of manager Jim Frey, to add power to his arsenal. Yet those two swings of the bat defined his legacy and made believers of Cubs fans who had never stopped wailing over the team’s infamous 1969 collapse.

“It was really the only two swings that I believe in my whole career that I aimed a half a foot underneath the baseball,” Sandberg told the Chicago Tribune in 2024. “The reason being that we were down, there was nothing to lose in that situation, everything to gain and that’s the plan that I went with. As it turns out, it was just something totally different that I hadn’t done before.”

The Cubs did not have a storybook ending in 1984, which ended with a postseason collapse in the National League Championship Series against the San Diego Padres; nor in ’89, when Sandberg was part of the “Boys of Zimmer” team that also made a magical run to the postseason before bowing out to the San Francisco Giants in the NLCS.

The Cubs weren’t very good at all in most of his 15 seasons, finishing over .500 only three times. They even started 0-14 in 1997, setting an NL record for most consecutive losses to start a season, and turning the final year of his career into a long slog that memorably included Ryne Sandberg Day at Wrigley on Sept. 20.

It was an emotional celebration that gave Sandberg much-needed closure on a career that was briefly interrupted by a shocking retirement during the 1994 season, less than two years into a record four-year, $28 million deal. Nat King Cole’s “Unforgettable” played over the sound system as Sandberg, his wife, Margaret, and their five children walked around the field waving to fans. There were some laughs as well, since Sandberg was the ultimate clubhouse prankster. His teammates gave him gifts that included a pair of crutches, which Sammy Sosa and Bob Patterson presented during a ceremony at home plate.

“I truly lived my field of dreams right here at Wrigley Field,” Sandberg told Cubs fans.

That seemed to be the end. The only thing left for Sandberg would be his Hall of Fame induction, which happened in 2005 in Cooperstown, N.Y., where he delivered a stirring speech that criticized the products of the steroid era.

Then Sandberg did the unthinkable, asking Cubs Chairman John McDonough for a shot at managing at age 47. He had played for 12 Cubs managers over the years and told McDonough he was willing to start at the bottom rung, Class A Peoria, to earn an opportunity to one day manage in the majors. The assumption was it would be with the Cubs.

It was a done deal in winter 2006. A Hall of Famer was back at square one, starting from scratch and sharing the dreams of the 20-something players he would manage.

“We’ve talked about it,” Sandberg told Tribune reporter Dave Van Dyck at the start of the 2007 season. “I’m trying to get to the big leagues. We’re all at the same level. We’re all working hard and we’re all trying to learn. I’m doing that, just like them.”

Sandberg eventually worked his way up the ladder to Double-A Tennessee and Triple-A Iowa and was touted by the media as the heir apparent to veteran Cubs manager Lou Piniella. But that wasn’t in the cards, and Sandberg was disappointed to learn he would have to succeed elsewhere for a shot.

Third-base coach Mike Quade succeeded Piniella on an interim basis after Piniella retired during the 2010 season and was given the job full time after the season as several players lobbied the media for his return. The Quade experiment turned out to be a disaster, and he was let go by incoming President Theo Epstein in 2011 as the Cubs began their rebuild.

But Sandberg left for the Phillies organization after losing out to Quade for the Cubs’ job in 2010. After managing in the minors and coaching, he finally got his shot to manage in the big leagues in 2013 after Charlie Manuel was fired.

When he managed a game at Wrigley that August, Sandberg received an ovation from fans on a bittersweet day.

Asked before the game if he felt he had a fair shot to get the Cubs’ job after 2010, Sandberg said: “I was talked to, so, yeah, I guess so.” He added he had no ill will against the Cubs. When he carried the Phillies lineup card out to the plate, Sandberg asked the umpires if they wanted him to explain the Wrigley Field ground rules instead of vice versa.

It wasn’t the Cubs, but it still felt like home to Sandberg.

Wrigley was always a sanctuary for Sandberg, who returned in 2024 — with 11 grandchildren in tow — for a statue dedication, following a bout with prostate cancer that allowed him to see and feel the love fans had for him.

It was a triumphant return for Sandberg, who was healthy and happy after keeping fans apprised of his medical journey in his Instagram posts. The support he received was palpable.

“I felt it in my Instagram, and being at Wrigley Field on a daily basis — the comments, ‘Keep it up’ and all that,” Sandberg said after the ceremony. “That’s just medicine for me.”

The fight with cancer would continue, however, and he announced a recurrence of the disease in December. Though he was in good spirits in February in spring training in Mesa, Ariz., Sandberg was absent at Wrigley for most of this season as the Cubs got off to their best start in years. His Instagram post in mid-July explained he was spending time with family during his “challenging” battle but still watching the Cubs from afar and excited to “see Wrigley rocking like 1984” again.

It has been a long time since 1984. Wrigley has changed quite a bit since Sandberg and his teammates began to change people’s perceptions about the Cubs.

Old Yankee Stadium was nicknamed the house that Babe Ruth built, but Wrigley was around long before Sandberg arrived. So, no, he didn’t build Wrigley. He just made it cool again.

That’s what legends do.

____

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments