A terrorism label that comes before the facts can turn ‘domestic terrorism’ into a useless designation

Published in Political News

In separate encounters, federal immigration agents in Minneapolis killed Renée Good and Alex Pretti in January 2026.

Shortly after Pretti’s killing, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem said he committed an “act of domestic terrorism.” Noem made the same accusation against Good.

But the label “domestic terrorism” is not a generic synonym for the kind of politically charged violence Noem alleged both had committed. U.S. law describes the term as a specific idea: acts dangerous to human life that appear intended to intimidate civilians, pressure government policy or affect government conduct through extreme means. Intent is the hinge.

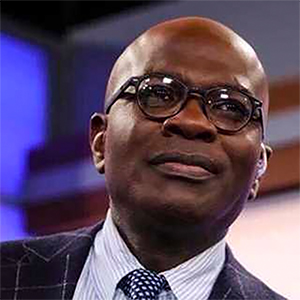

From my experience managing counterterrorism analysts at the CIA and the National Counterterrorism Center, I know the terrorism label – domestic or international – is a judgment applied only after intent and context are assessed. It’s not to be used before an investigation has even begun. Terrorism determinations require analytic discipline, not speed.

In the first news cycle, investigators may know the crude details of what happened: who fired, who died and roughly what happened. They usually do not know motive with enough confidence to declare that coercive intent – the element that separates terrorism from other serious crimes – is present.

The Congressional Research Service, which provides policy analysis to Congress, makes a related point: While the term “domestic terrorism” is defined in statute, it is not itself a standalone federal offense. That’s part of the reason why public use of the term can outpace legal and investigative reality.

This dynamic – the temptation to close on a narrative before the evidence warrants it – seen most recently in the Homeland Security secretary’s assertions, echoes long-standing insights in intelligence scholarship and formal analytic standards.

Intelligence studies make a simple observation: Analysts and institutions face inherent uncertainty because information is often incomplete, ambiguous and subject to deception.

In response, the U.S. intelligence community codified analytic standards in the aftermath of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. The standards emphasize objectivity, independence from political influence, and rigorous articulation of uncertainty. The goal was not to eliminate uncertainty but to bound it with disciplined methods and transparent assumptions.

The terrorism label becomes risky when leaders publicly call an incident “domestic terrorism” before they can explain what evidence supports that conclusion. By doing that, they invite two predictable problems.

The first problem is institutional. Once a senior official declares something with categorical certainty, the system can feel pressure – sometimes subtle, sometimes overt – to validate the headline.

In high-profile incidents, the opposite response, institutional caution, is easily seen as evasion – pressure that can drive premature public declarations. Instead of starting with questions – “What do we know?” “What evidence would change our minds?” – investigators, analysts and communicators can find themselves defending a superior’s storyline.

The second problem is public trust. Research has found that the “terrorist” label itself shapes how audiences perceive threat and evaluate responses, apart from the underlying facts. Once the public begins to see the term as a political messaging tool, it may discount future uses of the term – including in cases where the coercive intent truly exists.

Once officials and commentators commit publicly to a version ahead of any assessment of intent and context, confirmation bias – interpreting evidence as confirmation of one’s existing beliefs – and anchoring – heavy reliance on preexisting information – can shape both internal decision-making and public reaction.

This is not just a semantic fight among experts. Most people carry a mental file for “terrorism” shaped by mass violence and explicit ideological targeting.

When Americans hear the word “terrorism,” they likely think of 9/11, the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing or high-profile attacks abroad, such as the 2005 London bombings and December 2025 antisemitic attack in Sydney, where intent was clear.

By contrast, the more common U.S. experience of violence – shootings, assaults and chaotic confrontations with law enforcement – is typically treated by investigators, and understood by the public, as homicide or targeted violence until motive is established. That public habit reflects a commonsense sequence: First determine what happened, then decide why, then decide how to categorize it.

U.S. federal agencies have published standard definitions and tracking terminology for domestic terrorism, but senior officials’ public statements can outrun investigative reality.

The Minneapolis cases illustrate how fast the damage can occur: Early reporting and documentary material quickly diverged from official accounts. This fed accusations that the narrative was shaped and conclusions made before investigators had gathered the basic facts.

Even though Trump administration officials later distanced themselves from initial claims of domestic terrorism, corrections rarely travel as far as the original assertion. The label sticks, and the public is left to argue over politics rather than evidence.

None of this minimizes the seriousness of violence against officials or the possibility that an incident may ultimately meet a terrorism definition.

The point is discipline. If authorities have evidence of coercive intent – the element that makes “terrorism” distinct – then they would do well to say so and show what can responsibly be shown. If they do not, they could describe the event in ordinary investigative language and let the facts mature.

A “domestic terrorism” label that comes before the facts does not just risk being wrong in one case. It teaches the public, case by case, to treat the term as propaganda rather than diagnosis. When that happens, the category becomes less useful precisely when the country needs clarity most.

This article is republished from The Conversation, a nonprofit, independent news organization bringing you facts and trustworthy analysis to help you make sense of our complex world. It was written by: Brian O'Neill, Georgia Institute of Technology

Read more:

Clergy protests against ICE turned to a classic – and powerful – American playlist

Congress has exercised minimal oversight over ICE, but that might change

Federal power meets local resistance in Minneapolis – a case study in how federalism staves off authoritarianism

Brian O'Neill does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Comments