Congress ponders reforms in Medicare program at the center of DOJ's probe into UnitedHealth

Published in Political News

UnitedHealth Group’s confirmation of a federal probe into its Medicare business comes just as lawmakers in Washington are newly calling for reforms in the sprawling Advantage program, which now provides coverage for a majority of Medicare beneficiaries.

For years, Medicare Advantage, or MA, has been a lucrative line of business for private health insurers. But questions about an arcane, technical process called “risk adjustment” — the issue that’s currently snagging UnitedHealth — have spurred a series of scolding federal audits and at least one large financial settlement between another insurer and the federal government.

The pressure on MA is undeniable and could drive changes that effectively turn out the lights on what critics have described as a taxpayer-funded party for health insurers.

Yet it’s also true that MA has been hugely popular with seniors, meaning any changes made for Medicare program integrity, experts say, will run up against concern about financial side-effects for beneficiaries.

“I wouldn’t say the party’s over – I think people are just getting rid of the open bar,” Michael Chernew, a professor of health care policy at Harvard University who studies the economics of Medicare, said in an interview earlier this summer.

In the MA program, seniors elect to receive their standard Medicare benefits for doctor and hospital care, plus prescription drugs from a private managed care health insurer. The private insurers can set rules for where seniors get their covered services as well as administrative controls to check whether recommended treatments are justified.

Risk adjustment is the process in which MA insurers submit data on the health status of enrollees to justify higher payments from the government for covering their care.

It’s a key part of the program because health insurers otherwise would have a financial incentive to avoid covering patients who need expensive care. But it’s also where the controversy comes in for UnitedHealth Group and other industry players.

Last year, a report from the Office of Inspector General at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found UnitedHealth Group stood out from its peers — but wasn’t alone — in using questionable diagnosis data to boost MA risk adjustment payments by billions of dollars.

In September 2023, the Connecticut-based health insurance giant Cigna agreed to pay $172.2 million to resolve allegations that it violated federal law by submitting and failing to withdraw “inaccurate and untruthful” diagnosis codes for its MA enrollees to increase its payments from the federal government.

Calls for change within MA came just this week, as subcommittees on Health and Oversight at the House Ways and Means Committee held a joint hearing to examine lessons learned after more than two decades of the program.

MA, which was launched in the 1990s and expanded in the mid-2000s with bipartisan legislation for the Medicare Part D drug benefit, now covers a majority of Medicare beneficiaries. Some lawmakers have zeroed in on the program’s risk adjustment funding, in particular.

“The most effective step the (Trump) Administration can take in cutting waste, fraud, and abuse in federal health care programs is by reining in the wasteful practices of corporate health insurers in the MA program,” Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren wrote in a March letter co-signed by Minnesota Sen. Tina Smith and six other Democratic senators.

The letter did not name UnitedHealth, but the company is the nation’s largest MA insurer. Senators asked HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. to further crack down on alleged “upcoding,” where insurers are thought to manipulate diagnosis data to make patients look sicker and gain more federal dollars.

“The challenge is: Anything you do to tighten up risk adjustment can have an impact on the benefits that people get,” Chernew said. “The questions are: By how much, and which benefits are affected? Program integrity is an important goal, but I don’t think anybody wants to destroy the Medicare Advantage program.”

UnitedHealth Group, which runs UnitedHealthcare, the nation’s largest health insurer, has long defended the MA program and continues to do so.

“MA plans do a much better job of identifying and documenting health risks than traditional fee-for-service Medicare, which is driven by MA plans’ focus on proactive and coordinated care models that identify, document and treat chronic conditions early on, which leads to better health outcomes for those we serve,” the company said in a December statement.

“There is well-established research that documents these differences between Medicare and Medicare Advantage, and which underpins the regulations used to pay MA plans for the cost of providing benefits to the populations they cover.”

Insurers argue the large MA market share, which has built steadily over the past two decades, speaks to the popularity of the coverage. It has been chosen by nearly 35 million seniors and individuals with disabilities nationwide, according to AHIP, the trade group for health insurance companies.

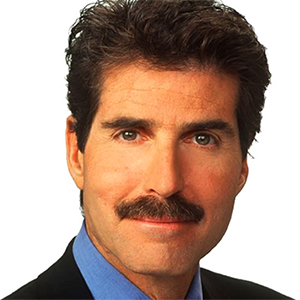

At Tuesday’s congressional hearing, Rep. Lyle Doggett, D-Texas, quoted the oft-viewed viral video of a Texas plastic surgeon who said a patient was on the operating table when a message arrived from UnitedHealthcare with a question on coverage for the procedure.

“Stories like hers are why I’ve asked the Justice Department to expand its investigation into United,” said Doggett, who serves as the highest-ranking Democrat on the Ways & Means Health Subcommittee.

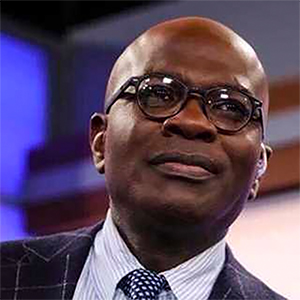

Rep. David Schweikert, an Arizona Republican who has introduced legislation to reform aspects of MA, noted some insurers resisted providing information on coding data for Medicare beneficiaries. “I will argue that ... the incentives are misaligned,” Schweikert said.

In advance of the House hearing, AHIP argued that MA plans deliver coordinated care, substantial cost savings and comprehensive benefits that far exceed what’s provided under Medicare’s original fee-for-service program.

Medicare doesn’t have a cap on out-of-pocket spending, AHIP noted, whereas MA plans limit expenses annually. People in original Medicare often handle this risk by buying “Medicare supplement” policies, but premiums often far exceed the cost of an MA plan.

“It is clear that Medicare Advantage is working for the beneficiaries who choose it,” AHIP said in a statement. “The question for policymakers is how to build upon its proven success to meet the health care needs of an increasingly diverse and growing population even as the underlying cost of care continues to increase.”

_____

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC

Comments