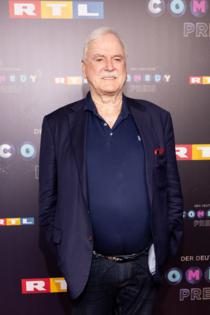

Q&A: John Cleese celebrating 50 years of 'Monty Python and the Holy Grail'

Published in Entertainment News

SAN JOSE, Calif. — John Cleese took a big risk when he helped create “Monty Python and the Holy Grail” back in 1975, as the idea of a series of parody sketches centered around King Arthur seemed absurd compared to comedy of the era.

But it’s the absurdity that made it such a hit.

Fifty years later, Cleese, now 85, is still meeting new people who were moved by the film, and he’s just as excited as ever to talk about what it was like to make it, and the impact it’s had on the comedy world.

Cleese is screening the film for audiences, followed by a Q&A, on his "Not Dead Yet!" tour marking the 50th anniversary of "The Holy Grail."

Cleese sat down with the Bay Area News Group to discuss what it’s like to interact with modern comedy fans who are attracted to the 50-year-old film, and what needs to happen in order for new comedies to continue pushing the envelope the way Monty Python once did.

[This interview has been edited for clarity and length.]

Q: John, how are you doing these days?

A: I’m pretty strung out. I just flew in from London last night and it was one of the most uncomfortable seats I’ve ever been on in an aircraft. Unbelievable. And it’s a 10-hour flight. It was awful. And discussing it with the crew, one of the things that makes me mad to think about is how decisions are made about design without other people being consulates. It’s that stupid arrogance.

Q: That reminds me of a quote said by your Emmy- Award-winning character, Dr. Simon Finch-Royce, on the sitcom, “Cheers,” in 1987, when someone asked you, ‘how was your flight?’ And you responded, “Relatively crash-free.”

A: (Laughing) That was one of the best scripts I’ve ever had. Written by the Charles brothers.

Q: When it comes to Monty Python, you must be weary after talking about it for 50 years, no?

A: Not really, the questions are always slightly different, and I learn different things. I learned a lot about laughter in the last 15 years and how important it is for people. So I regard laughter as essential now rather than as a luxury. As my views change my thoughts change.

Q: When you interact with people who loved Monty Python, has the stuff they loved about it changed over time? Or have the people who love it changed?

A: It delights me that there are so many people, 30-somethings, and a lot of them say, “When I saw Monty Python it opened the door to a new world.” People had never seen that kind of silliness. Some of it is very intelligent too. People hadn’t seen it. Suddenly they got very excited because they thought, “I like this. I like this new way of thinking and a general skepticism of why people are doing things.”

When King Arthur says, “I am King Arthur,” and the peasants say, “Well, we didn’t vote for you,” those are big questions. The lovely thing is, all these people often have tears in their eyes when they say, “thank you for making me laugh.” And it’s because laughter is good for us. It’s good physiologically.

One guy in Sweden told me when he left for the show, his blood pressure had been 184. When he got back it was down to 148. It was an extraordinary drop in blood pressure because he sat there and laughed for two hours. People don’t talk about that enough.

People used to say, “laughter is the best medicine.” It helps a lot. And it makes me feel like I’m doing something that’s really useful rather than something that’s just pleasurable.

Q: Instead of sending people to the hospital perhaps we should send them to a comedy show.

A: Well there’s a guy called Norman Cousins that claimed he cured himself by watching comedy. He put a room in all hospitals where people could go and watch comedy videos. People used to use them. But you don’t hear this stuff because it’s not materialist science so it doesn’t count. Scientists sweep it under the carpet if it’s anything they can’t explain.

Q: When Monty Python first came out, a lot of people said, “Wow this is something different.” The way things get made these days, where studios may be more drawn to projects that match the algorithm of a sure thing rather than taking a risk on something different, is it difficult for younger folks trying to do something different the way you were with Monty Python. Do you talk to young folks trying to be different in comedy?

A: I do, and as far as the BBC is concerned, I’m absolutely appalled. It’s as though it’s set up to crush creativity. It’s as though the executives want to be the creative people and want to be the stars and to tell people what sort of shows they’re looking for.

Whereas what you should do is you find somebody very talented and say, “what do you want to do?” And you facilitate it. That’s how you get great shows.

Ego screws up most of the things in this life. You have no idea how stupid a lot of these TV executives are.

You won’t believe this story but I met someone who said, “I was on a weekend holiday and I met some American executives and they said they just bought the rights to “Fawlty Towers,” and I said, “I’m delighted. Can I help?” They said, “no they don’t need help.” I said, “well do they need to change anything?” And they said, “no we’ve already made one change” And I said, “what’s that?” And they said, “we’ve written out Basil (main character Basil Fawlty, played by Cleese).”

That’s off-the-scale stupidity. And of course it was a disaster because they had no idea what they were doing. I could go on for a long time about this but I think this is generally true: there’s an enormous number of people in charge that don’t know what they’re doing. And the trouble is ego.

Q: You literally wrote a book on creativity. If you were giving advice to comedy writers trying to be creative in the modern world, what would you tell them?

A: I tell people how they can become better writers. I have certain little exercises I share with them.

But I say, if you are handing scripts in to people who don’t know what they’re doing — there’s a guy at the BBC who I met recently who was commissioning comedy scripts who was a complete idiot — what does a young writer do if they hand a script over to someone who he assumes knows what he’s doing, but he gets criticism or suggestions what are completely wrong?

I remember talking to Disney once and they loved a script I had done, and they said, “will you make some changes in the next couple of weeks?” And I said, “I’m afraid I can’t.” They got very surprised. Why can’t you? I said, “I don’t know how to make the script worse. I’d be trying to make it better and that’s not what you want.” So of course that was the end of that.

My general feeling is executives think they know what they’re doing, but they don’t.

If they said, “we don’t really know, but we’re going to facilitate people who have real talent,” well then you’d get something better than if they try to be creative themselves. Leave that to people with creative talent.

You can tell I can get quite worked up about this.

©2025 MediaNews Group, Inc. Visit at mercurynews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments