Why Alamo's preshow is one of the last, best reasons to go to a movie theater

Published in Entertainment News

CHICAGO — The Alamo Drafthouse Cinema, located in the new plastic heart of Wrigleyville, tucked alongside the crush of tourists and bachelorette parties and bar crawls and soulless developments, is not the first place I would I think I would want to arrive early. And yet, I have to, and get annoyed when I don’t. Not because of the food they serve (not bad, not cheap). Or lines at the box office (nonexistent, that being a pre-pandemic concern). You must arrive early — 30 minutes before a movie’s showtime — just for the Alamo preshow.

The preshow is a reminder that 75% of the magic of going to a movie is waiting for the movie. It’s a reminder of why you bothered to leave the house to watch a movie.

I’m not talking about trailers.

They show many, many trailers. But only after this preshow. (Whatever you came to see, as in most theaters, starts 20 or so minutes later than scheduled, preshow and all.) No, I’m talking about the 30 minutes of parodies and oddities, archival PSAs and music videos, dance party footage, old toy ads, history lessons, workout videos, Bollywood numbers, interview clips, film essays and whatever else Alamo cobbles together, usually tied to the theme of the movie you’re about to see. If you went to the hilariously sadistic “Final Destination Bloodlines,” you got Tom and Jerry cartoons and satiric educational training films. “Barbie” got a Greta Gerwig appreciation and vintage toy commercials and clips of Ryan Gosling dancing as a child performer. Captain America movies get a slow-burn Ken Burns-inspired retelling of the history of Marvel’s Captain America films.

Recently, I saw the new “Jurassic Park” and for 30 minutes before trailers, we got bizarro dinosaur films and a history of a Finnish metal band for children, Hevisaurus.

Showing up half an hour before a movie begins is a lot to ask of an audience, especially one that would rather be streaming at home. But in my household, when we go to Alamo, arriving too early is ritual, and since I have an 8-year-old who needs to see every unnecessary live-action Disney retrofit, that preshow is often the only highlight.

Alamo has been doing preshows since it began 18 years ago in Austin, Texas; as part of an expansion in 2023, it finally came to Chicago, was bought by Sony Pictures and now has a few dozen theaters across the country. It’s not the only movie theater in town that knows how to warm-up an audience just sitting there, getting comfortable, fiddling with phones, eating most of the popcorn before the movie starts: A few blocks away, the Music Box Theatre has had a live organist for ages.

These bonus flourishes seem minor, but they should be studied by larger chains that go sweaty touting their investments in laser projection and 4DX immersion and Dolby 3D soundscapes. A good preshow is so simple, low-tech and warm as to feel old-fashioned; it’s an amuse-bouche that acknowledges, yes, you have a perfectly fine TV at home, maybe even a better sound system, but, as Nicole Kidman says in her famous preshow speech for AMC Theatres,“We come to this place …”

Keeping the audience in an anticipatory spell as long as possible — that’s the point.

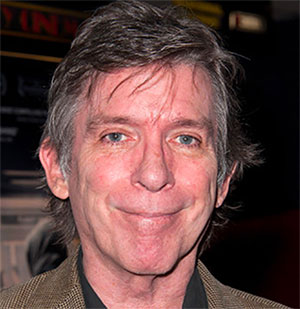

Tom Cruise, Kidman’s ex-husband, knows this, too: Before “Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning,” he greets the audience in a short clip, thanking them for doing something so communal. Cruise, on a one-man impossible mission to save the theater experience even if it means hanging off a biplane, delivered a similar preshow before “Top Gun: Maverick.” That these people go to such lengths in the service of framing another perfectly entertaining though forgettable night at the movies is what makes the preshow, often playing before the forgettable, so touching.

I don’t remember a lot about “Final Reckoning,” for example, but I remember Alamo’s exhaustive primer of 30 years of “Mission: Impossible” plots and MacGuffins. Without a disassembly, I would have been as lost as I bet a lot of audiences were. It also got me more invested in the experience than I had expected. Like Cruise, the Alamo preshow knows the last thing we want in the streaming age is to leave home then feel nothing.

Preshow entertainment, of course, goes way back.

In the first days of cinema, movies themselves were preshow entertainment, a kind of intermission between live vaudeville acts. Once features were the main attraction, there were cartoons, newsreels, shorts. During the Great Depression, to lure people back, theater owners in the Midwest would have giveaway nights, awarding dinnerware and even pets. Disney wildlife shorts preceded Disney films. As drive-ins became popular in the 1950s, theaters focused on concession stands: That iconic “Let’s All Go to the Lobby” spot starring dancing hot dogs and popcorn bags may be the most famous preshow entertainment ever. For decades, the Showcase Cinemas chain was known for sending ushers into theaters, shaking cans and soliciting change for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. But gradually, advertising took over. Trailers were the whole preshow, alongside traditional TV ads, PSAs about theater policies, and in the late 1970s and early 1980s, even lobbying campaigns from theater owners spooked by cable TV, warning of the death of “free TV.”

Laird Jimenez, the director of video content for Alamo, thinks of their preshow as continuing the older tradition, rarely practiced now, fed by the online libraries of archival footage and original video floods that the 21st century has been awash with. (Alamo gets permission, though does not pay, the creators of any material it pulls from YouTube or elsewhere.) But Jimenez also admits, they’re leaving money, a lot of money, on the table in the service of a theater experience. “(The preshow) is probably not the economically best decision considering the labor hours it takes to make them and the fact it’s screen time we could use — that’s money we’re losing, not running Chrysler ads.”

A recent poll of theater owners, reported by Variety, and conducted by analyst Stephen Follows and the online trade publication Screendollars, found that more than 55% of movie exhibitors believe the movie theater, as an institution, has maybe 20 years left. And still, other than movie trailers, Alamo does not run advertising, as a company policy.

Instead, as Rome burns, a team of three young guys in its Austin headquarters, with backgrounds in film school, film preservation, video stores and film festivals, pump out five to 10 30-minute preshows a week. There is some recycling, but almost every new movie that opens — as well as older repertoire films it shows, such as “Jaws” and “Mean Girls” — gets a new 30-minute preshow.

“A lot of original pieces we make simply come out of a passion we have for something,” said Ray Loyd, senior content producer. So, instead of car ads, you get a history of Black westerns, relayed by Black film scholars. Or an old TV spot with George Takei, in Sulu regalia, shilling for the Milwaukee County Transit System. Or a study of how “Dune” influenced ‘70s progressive rock. Or director Edgar Wright explaining the nuances of car chases. Or an essay on questions left by “Cats,” including: If cats have fur naturally, why do cats in the film “Cats” wear fur coats?

The recent “Nosferatu” got an extensive history of the vampire genre. “My favorite stuff is when we can show the breadth of everything in movies,” said Zane Gordon-Bouzard, an Alamo video producer. “We have this platform and we can show people there is a rich world of not only cinema, but videos, old TV — all worth preserving and watching.”

The result, sitting there waiting for your movie, is like having a friend show you this cool YouTube sketch, and now this insane commercial, and now this weird music video, then stopping to describe how “Lilo & Stitch” fits into the rich tradition of knockoffs of “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial.” Surprisingly, in this instance, with an audience, it’s worth the ticket.

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments